More...

Whether you're recording, mixing or mastering your music, compression is one of those basic (but seemingly complicated) audio concepts that you just need to understand.

Even if you're just demoing or writing with your computer/DAW and hire someone else to produce it, you'll find it very helpful to know what compression can actually do to your music as a whole and to specific individual tracks, what it can and can't fix and how you can use it creatively.

You'll be able to communicate better, understand the whole process better and develop a sonic vision that can be brought to life. You'll also gonna be able to avoid unwanted side-effects and address problems that might have been caused by using too much or the wrong type of compression.

Let's jump in!

This episode was edited by Thomas Krottenthaler.

TSRB Podcast 061 - Compression

[00:00:00] Malcom: [00:00:00] You might think that you're recording in your kitchen and it sounds fine, but as soon as you throw a presser on there and the sloppy ambience, if you're tiled kitchen, floor and backsplash and stuff gets louder, all of a sudden your vocals going to sound really rude and off,

Benedikt: [00:00:16] this is the self recording band podcast.

The show where we help you make exciting records on your own, wherever you are, DIY stuff. Let's go.

Hello and welcome to. The self recording band podcast. I am your host Benedictine, and I'm here with my friend and cohost, Malcolm owned, flat heart. I'm great, man. How are you? I'm great. Thank you. Awesome. Pretty excited because it just launched the Academy. As some of you listeners might know. Um, it's been a wild week, like when you're listening to this, it's already a week ago, but as of like today, when we're recording this, we just closed registration and it's yeah, it's pretty exciting.

Pretty exhausting, [00:01:00] but

Malcom: [00:01:00] something you've been working on for a long time. Yep. That's very cool. Yeah. Yeah. And thank you to all the listeners that have been, uh, listening along the way and anybody that did that buy the course. Um, I'm sure you're gonna love it. It's yeah, this is exciting. Great work, dude.

Benedikt: [00:01:15] Thank you. It's it's totally exciting. And it's so cool to see what came from this idea from this blog and then podcasts and then community and all of that. And, uh, yeah, it's just only possible because if you like the listeners and people who were joining the Academy now, probably because of like listening to the podcast first or checking out our Facebook community.

So thank you to all of you. And, uh, we're going to open up the Academy again and you will know, uh, I will let you know when it's time. Uh, but for now, we'll just keep on with our regular content as always. That's not going to change also. It's not going to change the free Facebook community. So if you want to join that, go to the set of recording band.com/community.

It's constantly growing. We have great conversations in there every [00:02:00] now and then we even have like, Live webinars. We just did one, which was very great. We don't know what we will do in that regard, in the future and how we're going to do it, but we're thinking about ways to be more engaged with the community and offer more value even for free.

So go to the self recording, band.com/community shine, the Facebook community, and, uh, yeah. We are very excited to see you in there. Definitely. Yeah. So today we're going to start something that we haven't done so far. We going to start a little, I dunno if it's going to be a serious, but we're going to do episodes, um, from now on every now and again that are about basic concepts, basic audio concepts, like explaining.

One specific thing, one specific part of the process or one specific technique. And we're going to start today by talking about compression because compression is one of those things that you need to understand whether you use it yourself or whether you, maybe you don't use compression while you record, but you still, I think it's still valuable [00:03:00] to know how compression works, because when you send in your tracks to someone else, they're going to use compression and you probably want to know what is happening.

To your tracks, you, I think it's helps you understand why things sound the way they sound after you got to expect, for example, or a master. So this is going to be the first of a couple of episodes. And, um, yeah. What are your initial thoughts, um, about like when you, when you hear the term compression, is this because I love compression so much that I.

Wanted to do this first. So what about you, Mike? What is like, what comes to mind when you hear?

Malcom: [00:03:36] I mean, I love compression too. Um, but I think a lot of people probably are glad we're doing this because I remember when I had no idea what a compressor was. Other than that, I thought they were cool and that I should be using one.

Um, cause that's the term that is constantly thrown around. Um, you'll see it anywhere. You can't Google anything to do with recording audio and not see the term compression somewhere in there. Um, so [00:04:00] what is compression, I guess, is where to start with this, right. Um, and compression is the process of reducing the dynamic range of an audio signal.

And I mean, that's technically what it's doing, but why we're doing that might be totally different, um, than just that. But essentially a compressor is going to take an audio file and squeeze it so that the loud and the quiet stuff is closer together. That's really what's happening at the end of the day.

So I guess now knowing that we need to try and describe why you would even want to do that. Like, why is that right?

Benedikt: [00:04:38] Yeah, yeah, exactly. I mean, yeah, th that expedition is, is pretty, pretty spot on. And I just want to say before we move on that, Don't confuse this with, um, compression with data compression, because I just need to say that because I had that a couple of times when people hear like a compressed audio file and they mean like an MP3 or whatever, like this is a different thing.

[00:05:00] Like it would not, we're not talking about that. That's we talk about audio compression, like the process of using a compressor to change the way. As signal sounds to change the dynamic range of a signal. It's not the same as compressing away files so that it becomes an MP3. It's a different thing. I just want to say that.

Yeah. Yep. Yep. So, yeah. Um, reducing the dynamic range. Uh, I don't know if you're familiar with the podcast, the attack and release show, shout out to them. It's a great podcast. It's two mastering engineers, Sam Moses, and. Um, I forgot the other name, Matt, I think, sorry for that. But like, yeah, the attack on the re and really show it's a great podcast about mastering and Sam, Sam Moses, the host of the show always refers to compression as more loud, more often because like in mastering, uh, especially because what happens is you push down on the loudest parts of a signal.

You. Make the loudest parts of a signal quieter, and then you turn up the whole signal. So the quieter parts [00:06:00] become louder. So all the stuff that's was quieter before is now louder. And so the whole thing becomes more loud, more often, and sounds louder as a result. But the peak level you're going to see on a peak meter is going to stay the same if you're using like a limiter, which is an extreme form of compression, but that's like the.

Basic explanation of it. You making the loud parts quieter than you bring up the whole signal to make up for that reduced volume. Yep. And by that you increase the perceived volume of the whole thing because the quiet parts get louder. Yeah, definitely

Malcom: [00:06:31] the, the overall loudness is now consistently. And I think that is really.

Like the really standard definition is the main reason, or at least the first reason to why we would use a compressor, um, is that we want to have a more consistent leveled audio file. Um, of, I think a vocal is probably the easiest thing to imagine that on where we don't want the singer quiet for some words and loud for [00:07:00] others necessarily.

Right. If, especially if it's meant to all be very, kind of at the same uniform volume and the compressor is going to. Do a great job at trying to correct that issue for us. Um, at the same time, we probably don't want. Certain noises like, uh, like hard consonance is to just like spike up. And I feel like they're just stabbing the listener in the ears where the word that comes after is really quiet.

Right? So again, a compression could be used to kind of split the difference there and bring those back into the same

Benedikt: [00:07:30] dynamic ballpark. Great. So first reason to control and level overly dynamic audio, you can think of that as like an auto fader in a way. It's like if you set a compressor so that it controls only dynamic audio and mix, it gives you a more consistent level.

It's just like, you're like a finger on a fader, constantly writing it and making, uh, making it more consistent. That's what it does, basically, if you set it that way. So that's the first use of it. Um, vocals, great example for [00:08:00] that. You can also do that with, um, the drums. For example, if you set the compressor really fast so that it grabs all grabs all the transients, you can make.

Inconsistent kickers, snare hits more consistent and control the dynamic of that because that's a really dynamic signal. Right. Or, um, bass for example, needs to be controlled a lot often, just so certain notes don't champ us out as much and it's more consistent. So yeah, controlling and leveling over lead dynamic audio, we kind of already touched on the next, why, which is to shape transience when you were saying like, Controlling plosives and vocals, or when I was talking about drums, right?

We're talking about transients with trucks, talking about the initial attack of a signal. This could be a pick attack of a guitar or bass. This could be the stick attack of a drum. This could be plosives and a vocal, like all these sharp, short, um, peaks in a signal that are, these are called transients.

And we can not only control them, like, um, clamp down on them and make it more [00:09:00] consistent. We can change the way. They sound, or we can change the relationship between the transient and the rest of the signal. So we can set a compressor so that it gets rid of the transient or much of it we can set in the way that it like brings out the transcend even more and makes it snappier, punchier.

Both of that is possible. And we're going to talk about the, how, uh, in a second, but. Just know that this is another, um, way or another reason to use a compressor. You might not make the whole performance more consistent, but you can shape. The way the attack

Malcom: [00:09:35] sounds. Yes. Yep. So yeah, the attack, when we say attack, we're usually also saying transient transient attack are kind of the same word in that sense and transients a great word to know it'll come up a lot.

And it's good to think about as you're getting sounds in the studio too, is like, okay, what is happening with the transient information when I make it like this? Um, on any instrument, especially drums, I think. Um, [00:10:00] and yeah, I mean, again, we talked about just a, I think an important thing to differentiate is that we talked about using a compressor troll levels and like maybe make the transient sound quieter or louder.

Um, but it's also like a total totally a tone shaping. Tool as well. Um, like you can really alter how the transient sounds and, and rounded off, and it'll totally transform like a snare drum, for example, will sound dramatically different with a fast or slow release or sorry, attack releases are coming next.

But think of that as the start of a drum hit or the start of a sound, um, where, um, next would be. Using a compressor to alter the sustain of signal. So again, sticking with the snare drum for now, the initial attack is the big spike, right? Like right when the stick hits, there's a transient. And then there's the decay of the drum after.

Wow. Yeah. Nothing if you have, yeah, that wasn't so,

[00:11:00] uh, Yeah, that is the transit. And then what would be the, that sustain? You joined the spending. Do you want it together now?

Um, so the sustain is, uh, in this case pretty long. Uh, and now using a compressor, though, you can alter that you can make it. Duck quicker or, or stay, um, like try and make it louder even. Um, and you kind of have some control over if the sustain of that drum sounds as you recorded it pretty much like, or as it does in the room, you can make it try and adjust it to be shorter or longer, um, using a compressor.

So you, with a compressor, you have control over. I guess dynamics, but like the, the shape of the transient and the sustain of

Benedikt: [00:11:53] the sound as well. Yes, totally. And in a weird way, it's not either, or it's like when you [00:12:00] change the, the transient, like it sort of changes the sustain or the way you perceive the sustain and vice versa.

So sometimes you don't actually do anything to the sustain, but it sounds different because you like altered the, the attack a lot. Or what about we get, we get to that. So in almost every setting, a compressor changes the attack and release like the, the, the, the transient and the sustain. These are the correct terms in this, um, when it comes to this.

So, yeah. Um, Let's maybe so that people understand what we're talking about and how this actually works in happens. Let's talk about how, how it's done. And I just, um, set the correct way to call these things is trend transient and sustain because attack and release. I don't want to confuse this because of tech and release all the controls on the compressor that are typically called attack and release.

And, um, it's not. That when you turn the attack up, you're going to get more attack, for example. So that's, that [00:13:00] can be a little confusing. The first part of the signal that sounds like the attack of it is called transient and the sustain is called sustain. Everything that comes after that, and the controls are called attack and release.

And we, what we can do with these, that's what we're going to talk about now. Awesome. So we we've explained what the compressor. In general, does a compressor makes the louder parts quieter and then we can make up for the difference and increase the level of the whole signal. We need to start with the threshold because the threshold is what tells the compressor when to actually start changing the signal, like how loud is too loud.

Like, you know, at what point should the compressor start making the last of quieter? You telling the compressor, if the signal exceeds this level, You got to do something about it.

Malcom: [00:13:51] As Benny said, the threshold will. Decide the point that the compressor actually engages. Um, and [00:14:00] what that means visually. I think this is the easiest way to picture it is if you've recorded audio into a computer, you've seen your way for them displayed on the screen, going up and down, right?

And that's your, your signal. It's a representation of your signal. Now, the highest peaks that go the furthest up or the furthest down, those are the loudest parts of signal. And. If you imagine that you've got, uh, lines above and below the wave form and you start moving them closer to the way for them as you go, eventually they're going to start hitting the loudest peaks.

Right? So imagine that you're just like bringing these borders in, on your way for them. And as soon as it hits any of those peaks and your way for them, that's when the compressor is going to actually kick him. And that is our threshold. Our threshold is that line being brought down onto the peaks of our audio.

And obviously if you just max it out, All of the audio would be triggering the compressor, but you can really decide what using the threshold, the threshold control. You can decide how much you want to be taking, um, the, [00:15:00] how much you want to affect it by the compressor. Does that make sense to you? I'm using hand signals as we're having the zoom call?

Yes. Yeah,

Benedikt: [00:15:06] it totally makes sense. I just, I'm just not sure if like, because the visualization really helps, but it doesn't really tell the compressor how much. To do, um, or to take away or to, but, but it's, it tells the compressor, like how loud is too loud, basically. Like when, yeah, when to start working basically, because how much it's going to do to the signal is determined by the ratio.

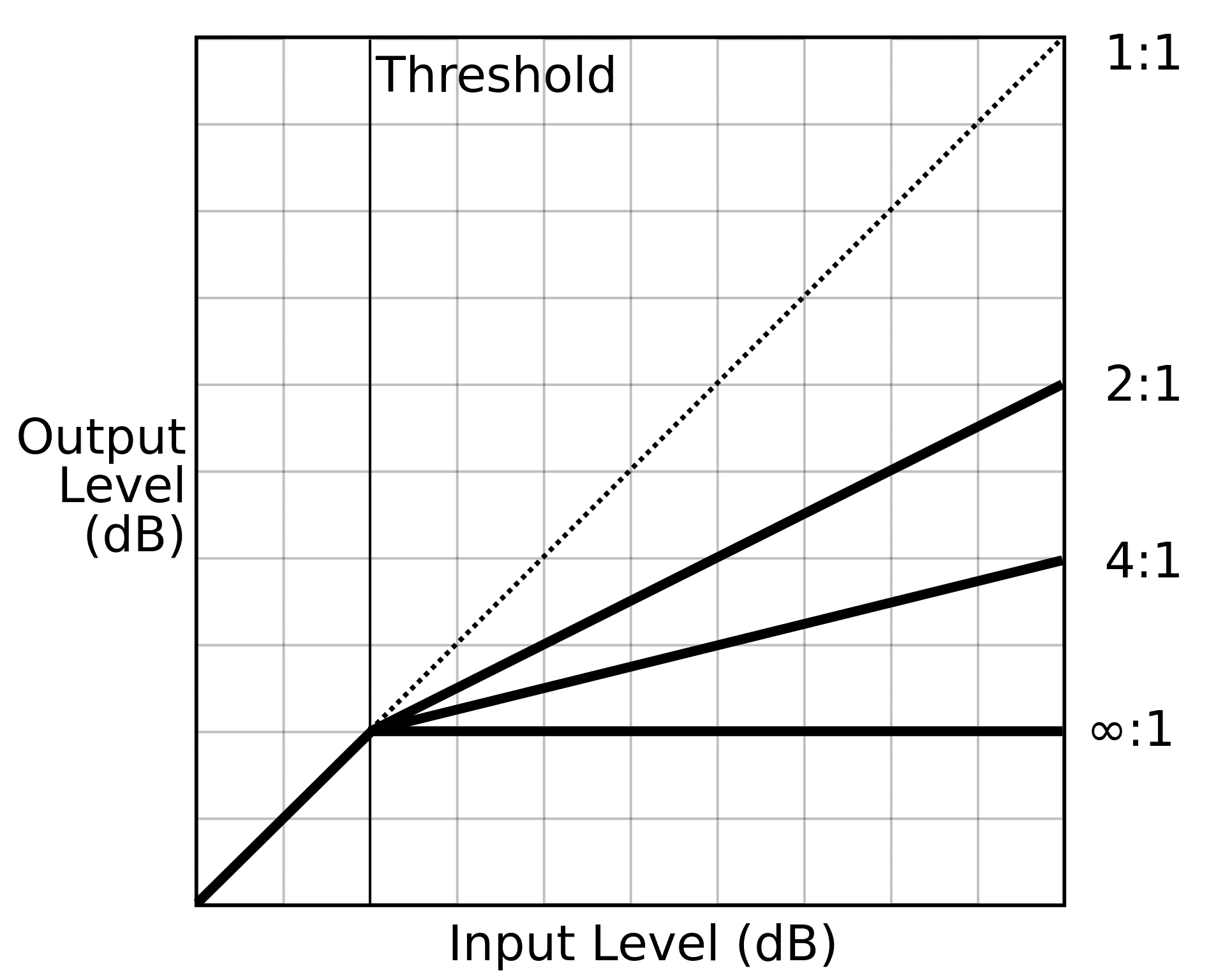

The ratio tells the compressor, like if the signal goes over this threshold, turn it down by this amount and you see the ratio control usually gives you options like two to one or four to one or 10 to one. I think we need to put in the show notes. We need to put graphs in there to like help visualize this.

Because if you're not seeing this, it's really hard to understand, but just know that the higher the ratio, like 10 to one compared to two to one, [00:16:00] Means that the compressor turns it down more after it goes past that threshold. And it turns it down in a certain ratio. That's basically what it does. So, um, once you see the graph, it totally makes sense, but it's just, um, yeah, it just tells the compressor how much to turn down the signal.

We can leave it at that, I think.

Malcom: [00:16:19] Yeah. Just there to give you an idea because you've probably seen them in Bolander and there's usually like a two to one, four to one. Um, and then those are the most common, but they do go higher. Of course. Um, and yeah, higher ratio is going to be

Benedikt: [00:16:33] more compression. Yeah. And two, maybe it helps.

It helps you understand all of this. If we tell you that a limiter has basically a very, very, it's a compressor with a very, very, very high ratio. So that as soon as the signal hits the threshold, it's going to stay there. Basically at this level. It's not going to go any louder. It's like a ceiling. This is basically, um, uh, the highest ratio possible.

And this [00:17:00] is what a limiter is. It's a compressor with a very, very, very high ratio. Yeah. So, and yeah, and, um, now it gets interesting because the attack and release is what's going to shape the whole behavior and the sound of our signal. Because as of now, we have told the compressor when to start working and we have told it how much.

To do how much to turn the signal down. Now we're going to tell it when to reach maximum gain reduction and how long it will take to let the signal come up again to where it was. That's what attack and release does is there's a misconception because a lot of blogs or YouTubers, or a lot of information out there, a lot of resources out there tell you that attack means the time it takes the compressor until it starts working, which is not true.

That's a misconception because a compressor starts working immediately. The attack time. Tells you how long it takes it to reach full gain reduction [00:18:00] to reach the full like right. Um, four to one, six to one, 10 to one, whatever you set. So it's not like that there's nothing happening. And then like if you have an attack off 20 milliseconds, it's not that the compressor doesn't do anything in those 20 milliseconds and then starts working.

It just means that it takes the compressor 20 milliseconds. To do what it's supposed to do, like to reach the full game reduction. And if it's set to even longer times, it takes it even longer. And if it's set to a very short time, uh, it's very quick, but it reacts immediately after the signal goes past the threshold important to know.

Absolutely.

Malcom: [00:18:32] Yeah. And again, this is really going to mess with your transient a lot. Um, the attack controls pretty much. How will you shape a transient. So keep that in mind. And that's what to listen for when you're experimenting with a compressor and trying to figure out what that attack does, listen to the transit information most,

Benedikt: [00:18:50] I think.

Yeah, exactly. Like, um, so what that means when you actually applied, when you actually try what, what it does, it means that the longer the attack time is [00:19:00] the more of your signal of your transient gets through. And, um, Without being compressed or turned down a lot. And as soon as that, that also means that quicker transients and high-frequency transients get through with shorter attack times while slower, lower frequency stuff like kick drums, bass notes, and stuff, they are going to be turned down and you have to increase the attack time in order to let a kick drum through, for example, Why you wilds, for example, a quick mouth click or, um, uh, maybe, maybe even a snare gram or some very quick sort of transcends can get through with a very short attack time already.

So, um, yeah, the attack time basically gives you a control over how much, uh, how much of the transient you want to hear and or how much of it you want to eliminate, or they.

Malcom: [00:19:57] Round off. Yes. Yeah, definitely. [00:20:00] You'll hear the term preserving transients, like, like, Oh, we want to preserve the transient in this, like the chance, the information in this master, and that is referring to attack, like setting the attacks so that it doesn't grab the, uh, and mess with the transient information too much, um, would be the, like the goal in that case.

Um, but. All of those examples were kind of put through the light of not wanting to mess with the transient, but sometimes you absolutely do want to mess with the transient. So it goes both ways. There's a time and a place for both of just completely alternating it or trying to make it as if you couldn't tell that there was a compressor on it.

Benedikt: [00:20:38] Both happened. Exactly. Like for example, with the snare drum, I think that's a really easy example to understand, and to try for yourself, if you have a snare drum and you want to make it punchier or more Peaky, whatever you want to call it, if you want to have more transient, more stick attack, you want to make the attack long enough so that the stick of tech comes through and then.

You want to apply full gain reduction. [00:21:00] And if you want to do the opposite, if you want to have it, like sit in the mix better and not chump out as much, not be as punchy, not be as Peaky or whatever you want to call it. Then you, you use a shorter attack time and make the compressor compress immediately a lot, which will like even out the transients, push it back in the mix a bit, probably, um, make it less punchy.

And yeah, and both can be desirable depending on the situation. So you can make a drummer seem like to be hitting harder, or you can create the opposite effect. You can make it sound softer, like harder and softer are basically good words to describe this along our tech time will result in a harder sounding snare drum.

A shorter attack time will result in a softer sounding snapped room. Yep.

Malcom: [00:21:48] There we go. Uh, so release. Yeah, I think that's up next. So yeah. Releases, how soon after the signal dips below the threshold that the compressor stops working? Yeah. Um, so I like [00:22:00] to think of it as like audio goes through a rubber band.

And how long does it take for the rubber band to return? Uh, yeah. I think I stole that off Joel, on a second. I'm trying to remember what video, but I was like, Oh, I could actually picture it now. That's so helpful. Um, but yeah. Do you want it to return quickly or slowly? And like we said earlier, that's going to mess with the sustain of the audio primarily, which again can really be great.

Um, we've got like a lot of. Rock guys in the community. It seems. Um, and if you have like a fast, double kick part, you really need those drums not to sustain very long because they're going to just kind of like get on top of each other, like this, just like this kind of thing. So we want to shorten the kitchen I'm in like a scenario like that often.

And release could be a great way of trying to

Benedikt: [00:22:48] accomplish that. Yes, but Le but in both directions, that's actually a complicated example because it could mean that you set the attack the release time, very short, so that the compressor recovers before the next hit and you don't [00:23:00] mess with the performance too much, or it could mean to have the release time set pretty long so that it.

Too short, too short on the sustain of the kick drum and to, to control the whole kick drum part. So that's, that's a very complicated example for this because both could, could work. So if you imagine like a single hit first, what the, what you could do with the release time is. So you say you have this kick drum example that Malcolm just said, you have a single kick drum hit and you set the attack so that the attack of the kick drum, the transient comes through.

So it's punchy and full, and the bass gets through the low frequency content. And then if you have a very quick release time, the compression will kick in and immediately release it again. Yeah. Uh, so the sustain of the kick drum would come up very quickly. So you get a heart attack. And then the it's like you, if you would turn up the fader really quickly after the attack and the sustain of the kick drum comes up.

If you increase the release time, the [00:24:00] attack comes through the compressor kicks in and then it stays down. So the, the sustain of the kick drum will be quieter. So you'll have a very punchy cake with a quieter sustain. If the release time is long enough to keep it down there, if it's short, you'll have the attack and then the release will come up.

The, the sustain will come up immediately. And now if you think of the double bass part, uh, slow release would mean that the, probably the first hit of that part would hit pretty hard. And then all the other kicks would be pretty controlled because the compressor just stays down. It keeps it down. And then a fast release would mean that every single hit would like.

Yeah, you would have more movement. You would have more attacks and like the release would come up after each attack and you would get like really, probably pretty messy. But also pretty dynamic sounding, um, double bass part, whereas alongside a release would cause the whole part to be more so. Yeah.

Malcom: [00:24:59] Yeah.

And you [00:25:00] can, I mean like often, sometimes people try and time it, so that it kind of always is it's like a quarter note or an eighth or whatever. Like the common timing of that pattern is on that drum kind of thing where it's like returning just before the next hit, you know, that's a sound in itself. Um, it all depends on what you want to do and honestly, don't be.

Like upset. If this takes you a long time to really wrap your head around, it took me a long time. That's for sure. And I still feel like I'm learning. Um, it's a compression is just like this thing that sometimes it does what you expected it to do. And sometimes it takes a little longer to get it there.

Benedikt: [00:25:36] Absolutely. Yeah. I agree. It definitely takes experience, but there is actually a great way. To learn how to hear compression and what it does and how and what the controls do. And, uh, I think it's from the book. What's the book called mixing with your mind? I think it's, it's one of the greatest books I've ever read on mixing and it's the author explains it in a, in a way that really makes [00:26:00] sense to me.

And you can, you can like follow this and try to see if, if, if that it makes it more clear for you as well, because what he says is you should, um, when you want to figure out out what the correct settings for a signal are, and you're not as experienced yet, you can do the following. You can set the. Uh, tech time to the shortest possible attack time you sat the release time to the longest possible release time.

And you set like to start, and then you set the threshold as high up as possible, and you set a really, really high ratio, like a limiter to the maximum ratio. So, and then you're going to bring down the threshold until the compressor starts working. You bring it down a lot so that you get a lot of compression, very fast attack, very long release.

Very high ratio. You bring the threshold down until you get a lot of compression and then you start increasing the attack time until you hear a transient come through and you will hear at [00:27:00] first you will hear a very sharp, short transient than the transient will get fuller, louder. And at some point the transient won't change as much because you've reached an attack time where the transit just comes through and nothing really happens to it anymore.

And then, you know, like how much of that transient do I want to get through? How much low-end do I want to come through? How much attack you can set the release time that, uh, the attack time, that way, then you grab the release time and you shorten it. And you make it so that the compressor recovers just for before the next hit, as a starting point, you make sure that like, if you have a drum kit, for example, a snare drum or a kick drum or whatever, or a vocal just set the release time in a way that it's musical, that the next important transit information still gets through.

And whatever you want to have controlled stays down. And then you're going to bring down the ratio to a point where it's not sounding like a limiter anymore, but, and that produces artifacts and like distortion, but like sounds reasonable and musical. And then you set the threshold to take away as [00:28:00] much as you want, but you can like go through these steps and really figure out what the attack does, what the release does, how much you want to compress.

And then at what point the compressors should start acting. But if you. Do it in this backwards way, sort of it really, at least for me, it really helped me understand what the controls do and how I should actually set the compressed time on a, on a sick, uh, the attack and release times. Right.

Malcom: [00:28:24] Yeah. Yeah.

That's a great exercise for sure. Um, told the, encourage you all to. To try exactly that. Just pull up audio and, and then experiment with parameters until you do hear

Benedikt: [00:28:37] yeah. Two extremes, because it really helps to hear the extremes. Don't don't do it in a subtle way. Like send it to the extremes and see what it does.

And everything else is like experience and also tastes like, you know, much of it. It's just not right or wrong. It's just

Malcom: [00:28:52] tastes. Yeah, definitely. All right. We've, we've hit threshold, which again was where the compressor we think starts [00:29:00] to think something that's too loud, uh, attack in this, how quick it's going to respond, um, to the technical, yeah.

It's technical description being how quick it responds to the. Actual gain reduction that you've set, um, and then release being the speed that it returns. Um, and then makeup gain, I guess that's where we're at here. Makeup gain is. So yeah, if you picture, you're hitting the peaks, right. With the threshold, with, uh, your threshold, yours hitting the peaks and it's knocking those down and now if you've done nothing else, It seems like your audio is quieter because you've just gained reduced all those peaks, right.

By whatever ratio you've said it to. Now, the important thing to do is to make use makeup gain, to kind of bring up the overall level to where it was before. Um, and then now when we bypass the compressor in and out, our audio sounds the same. Um, the same level, ideally, that's like the goal of that. And we can actually tell if we like what we're doing to it.

If we like how we're

[00:30:00] Benedikt: [00:29:59] changing it. Right. Absolutely. That's super important because you might think something sounds better, but it's actually worse. And you don't know because it's just, it just got louder or quieter or whatever, just so you have to use the makeup game to make sure you can compare properly and also keep your gain staging the way it was and all of that.

So, yeah, it's, as the word says, like the term makeup and you make up for the gain, you lost. During compression. Yep. Now there are some compressors that don't have some of these controls. So if you ever, if you've ever seen an 1176 or a plugin version of that, for example, you won't find a threshold control and that's, but it's the same principles apply.

Even with those compressors or an LA two A's even simpler. Um, you don't even have attack and release controls there, but the same stuff happens inside. It's just when you with a compressor like that, when there is no threshold control. If you turn up the input, you move the signal towards a set threshold.

And when it reaches the threshold, the compressor starts working. But it's the [00:31:00] same thing. It's just whether you bring the threshold down or turn the signal up before it hits the threshold. It's the same thing. Um, yeah, it's not the same thing, but it. There is a threshold. And when the signal goes past that the compressor starts working.

Um, it's just, you just use it in a different way, but the same stuff is happening. And when on an two-way, for example, you can choose between limit and compress. It's going to give you different attack and release times. Uh, it's going to make the attack shorter and the release quicker probably. And, um, it's just a one, one click thing to change those parameters versus having.

To set them yourself, but yeah. Right. So there's all sorts of different compressors, but inside it's, it's the same thing happening. It's just different

Malcom: [00:31:45] concepts. Yep. Yep. Same principle going on there. Um, like Benny said, limiters are just really extreme compressors. That's what's going on there, I guess like, Hmm.

I shouldn't say anything I'm going to regret, but I think transient designers are essentially [00:32:00] more or less, very similar,

Benedikt: [00:32:02] so many different concepts at this point of transient manipulation tools that I would be careful with that, but, but I believe something, I believe, yes, you are altering the transient and the S the release.

So it's, it's a similar process, but some form of attack and

Malcom: [00:32:17] release. Yeah.

Benedikt: [00:32:18] Yeah, but yeah, you changing the dynamics. It all falls into the category of dynamics tools basically. And. Um, that's what a compressor does. You can use a compressor, like a transient designer almost depending on how fast the compressor is, but you can definitely increase, um, the attack or, or decrease it and you can change the release.

So you can do similar things as with S with the transit designer. So, yeah, absolutely. So let's talk about some typical scenarios and why this is important to you, even if you don't use compression. Now, when you record, for example, why this could be important to you, for example, If you record drums, you record a snare drum and your drummer is not hitting very consistently or not [00:33:00] very hard.

And the mixer decides that he or she wants to get more attack out of the snare drum or wants to make it more consistent sounding. So they do what we just described, the set, the attack and release to achieve whatever they want to achieve. They pull the threshold down. They adjust the ratio and then they had just the makeup gain to make up for the gain they lost.

And what then happens is more now, more often, or the quieter stuff gets louder. So the high head bleed or the symbols or whatever you have in that snare drum mic as well. Will become louder because the snare drum is louder in that mic than everything else. The scenario will be controlled and the quiet stuff will just come up.

So what that means for you is if you record a snare drum in a way that you capture a lot of that Hyatt bleed, or a lot of symbols, or a lot of the room or whatever else is going on, this stuff will become more apparent now will become louder now. And it could [00:34:00] the up to the, to the point where. You have to do something about it to the point where you have to use samples or you have to gated really hard or do some whatever tricks to get rid of that bleed, which will make the drum sound more natural and all of that.

So if you want to have a lot of your natural snare drum, or if you want to keep the drums all natural and the mix, you've got to understand the concept of compression, because if compression is necessary to achieve the sound and the punch you want. Then you better make sure you control the bleed as much as you can in that mic because the bleed will become louder after it gets compressed.

That's one, um, one scenario where you absolutely need to know about

Malcom: [00:34:41] compression. Definitely. Definitely. Um, yeah, compressing on the weekend, there are hardware compressors, uh, which are obviously very fun and cool looking. Um, but usually pretty expensive. So I don't really expect most self-reporting bands to have one, honestly.

Um, So it's worth knowing that there [00:35:00] are usually compressors in your door that can be tracked through in real time without actually being destructive and actually doing anything to the audio file. They're just for monitoring only. Um, so. And that's amazing. That's like what a great way to be able to learn and experiment with compressor as well, recording without destroying and absolutely ruining a drummer.

Right. So told the, encourage you to, to do that and try and get the sound in your head using a dark compressor. Just make sure it is like a ultra low latency one. Um, that's not going to add latency to the drummer trying to play. Um, but yeah, so use that. You gotta really watch out for bleed. Um, we're going to talk about Gates on a future episode, but that's going to be really relevant to this as well.

Um, so I'm excited for that. I think vocals are the other thing that I'm like a hundred percent of the time I'm going to have a compressor probably. Um, right. Uh, cause vocals are extremely dynamic instruments. [00:36:00] They, they can be really quiet or really loud. It's kind of hard to, even for the singer, I think to self-regulate that, um, I don't I'll maybe I dunno, but essentially they're more dynamic than what we want to come in out of a speaker.

Um, usually, and when you put it in a mix with all of these loud instruments, like a distorted guitar, which is very constant and loud, That vocal getting quiet might mean that you can't hear it anymore. Right? So you get in a compressor on a vocal is something that's extremely common. Um, and the things to watch out there is I think continence is, might be the worst of them.

Um, if you set up your compressor wrong, you might end up with like S noises that are just insanely loud and hard to deal with. Um, and different people have different S noise. Characteristics. Some people are really prone to it. People don't have any, and that's a problem too. Um, so that's like a constant thing.

So you'll spend a lot of time dialing into the attack [00:37:00] on the, of the compressor and the release actually. Um, on, on a vocal, I usually suggest people start on a vocal with, um, all the way slow attack, all the way fast release. That's like safe starting point for, uh, Compressor to do something helpful

Benedikt: [00:37:17] on a vocal.

Yeah, I agree. Um, you're going to know that fast release. Usually, at least to me usually means it sounds more aggressive. Um, longer release sounds more controlled and even, and level out. And if you have four, a same with the singer, for example, a very quick release time, it's going to make the vocal chump out the speaker more.

It's going to pronounce the, yeah, it's going to be. It's it's imagined like the best example would be probably a wrapper or some, some sort of aggressive local, where you keep the attack long enough to get all the transcend through and the aggression and the, you can hear the singer, the rapper is spitting, you know, and then you have the fast release time.

So it recovers quickly, and it just sounds [00:38:00] explosive and aggressive and upfront. And that's also for rock vocals. Very, very helpful. And so, yeah, great starting point there. And also I feel it's very helpful to track with a compressor when you track vocals or at least monitor it because it makes the singer oftentimes feel much more confident because if you.

If you really compress it hard on the way in, or at least on the monitoring, then, um, it immediately, immediately sounds more finished, more upfront, more like a record, and the person singing. If they hear that on their headphones, they've, they're going to feel more confident about themselves and they're going to enjoy it more versus the very, very dynamic uncompressed signal that can sound weak to them.

Or they might start questioning their own performance or their energy or whatever. And when they hear this. Like pumping energetic, sort of over the top voice, it's going to make them more exciting. You've got to be careful though, to not ruin it, if you're not, no knowing what you're doing, but, um, at least have it in the monitoring, um, signal.

It really helps us. [00:39:00] Definitely.

Malcom: [00:39:00] Yeah. I totally agree. Um, yeah, that, those are like the two main use cases. I think. Um, I don't always compress guitars. I don't even always compress base in tracking most

Benedikt: [00:39:14] of the time I do, but not always. Yeah, you're right. But here's another thing why you, even, if you don't do it, need to again know about it or should keep it in the back of your hat, because when you're tracking bass, for example, and you play, let's say you play with your fingers and you have some really sharp, um, Like clacking sounds and there, which some fingerstyle basis have when they hit the pickups or they, they sort of sort of some basis pull on the strings and it makes these clacking attack noises, but not all the time, like inconsistently, if you get that, some, some people do that with a pick as well, but like finger style, bass.

I have had a couple of, of, uh, tracks sent to me that had this problem where there would be this occasional clicks and this, this overall clacky [00:40:00] sound. And when I then want to compress that, change the tone, or to make it more consistent or whatever these clicks and pops would jump out like crazy. And I would have to do something about them and control them.

And th this can be very tough to do, and I sometimes cannot compress as much as I would love to because of these things. So just keep in mind. That stuff that's not as obvious while it is uncompressed might become more obvious and more of a problem after it's compressed. So, yeah. Right.

Malcom: [00:40:29] That is a great thing to bring up for vocals again, actually.

Um, and another reason to at least monitor a compressor is because you might think that you're recording in your kitchen and it sounds fine. But as soon as you throw a compressor on there and like the sloppy ambience, if you're tiled kitchen, floor and backsplash and stuff gets louder, right? Because all the quiet stuff's getting louder as we're compressing and closer to our, you know, average volume, it gets.

All of a sudden your vocals going to sound really roomy and awful. [00:41:00] Um, uh, probably awful, I should say. Uh, and, uh, so yeah, I like that's for a self recording band. That's one thing I think that would be really great is to always slam a vocal a and C. What comes out, right? Like does the room all of a sudden activate and you're like, Oh my God, this is like an echo chamber.

All of a sudden kind of thing. It wouldn't be an echo chamber, but it will, you'll hear that room sound. Um, it's hard to describe that. That would

Benedikt: [00:41:26] be a wise choice. I was surprised how much, like how loud the room actually gets. I have a very, very controlled, uh, tracking room and it's, it's small, but it's very, very.

Controlled and dry. And still, if I really slam of Oakland, I still compressed at heart. The vocal that's been tracked at my studio. I can still hear that room. And I'm always surprised because when you're in that room, it's it feels static. It feels really, really dead. And I'm always surprised about like how roomy it can become after it's compressed and limited and distorted and whatever.

So yeah. Do that test and add like, think of that [00:42:00] scenario of, with your like tiled kitchen floor and, and everything, and add to the slap back, add to that, like your overly sibilant voice, maybe that you haven't realized you have. Um, then you were really starting to have a problem because then the SSR louder than you thought they would be the slap delay or the, the echo, the reverb is louder than you thought it was.

And all of a sudden, you end up with a mostly unusable vocal. That sounded fine to you and you didn't even notice, but yeah, yeah,

Malcom: [00:42:28] yeah. If you listen to podcasts that aren't recorded by us too, you probably hear this all the time. Like pretty much people that aren't either, uh, successful in that like Rogan's podcast sounds pretty great because he's got an audio engineer, like literally in the room with them.

Um, and other people will do as well, but a lot of people starting out just, you know, grab a USB mic, plop it down in their living room and then. You're like, wow, this is pretty terrible sounding. That's uh, that's kind of the sound we're describing. Yeah,

Benedikt: [00:42:56] exactly. Yeah. Cool. Um, I mean, [00:43:00] that's, that's a lot to, um, to process already, like for you probably, and I'm, I need to come up with a way I need to put something in the show notes that makes this.

Easier to understand and to visualize. So if you go to the show notes of this episode, which is the self recording band.com/ 61, you'll find additional info on this. Um, and I try to make it as easy for you as possible. And then I think the most important thing is just. Using what you've learned now and trying to interest, experimenting, trying to learn what that stuff sounds like, uh, trying to train your ears, to hear compression, to know what the controls do.

It's a lot of experimenting and you get there pretty quickly. If you do those exercises for a bit, like it's. It's well, it will become obvious to you now that you know what the basic controls do. Just experiment basically. Yeah,

Malcom: [00:43:51] definitely. Yeah. Cause there, there is more, um, like there there's more functions on some compressors than others and stuff like that [00:44:00] and stuff that you know is important and I use every time, but uh, until you've got this stuff down, it's totally irrelevant.

Benedikt: [00:44:07] Yeah, exactly. Also like what, probably the last thing I wanted to, I want to add here is. When you are getting a mixer, a master back, and you feel like it sounds flat, or it sounds not exciting anymore. And you don't really know what happens and you, you having a hard time describing to the engineer, what is wrong?

It could be that it's just over compressed. It's just that the transients, the peaks are not there anymore. And that's that it's because. And that's what makes it sound lifeless to you? Maybe there was a very punchy. Snare drum. And after mastering the snare drum was gone or maybe there were like exciting vocal transients and continents.

And now it sounds all flat or maybe like all these things, maybe there was a big full bass drum and now the low end is gone and it's not because they took out [00:45:00] the low end with the NICU it's because maybe they compressed it very hard with a short Ditech time or they used to limit or very hard. And now the, all the low end.

It's being controlled and probably distorted by the compressor. So now that you know what a compressor can do next time you get something back and you feel like it's not what it should be. Maybe you now have the vocabulary to explain to the engineer what's wrong. And the opposite could be true as well.

Maybe you want it more dense, more energetic, maybe something. They chumps out too much and you want to have it more controlled and you can tell the engineer, Hey, I got this overly dynamic, whatever, can you control that a little more? I have too much transients in here or whatever, just, um, I think it helps you communicate better and, uh, maybe get to the reason for a certain problem faster.

Right. Yup.

Malcom: [00:45:49] Yeah. Great point. All right. All right. I think that's a wrap. Thanks. So go play with

Benedikt: [00:45:53] compressors guys. Exactly. Okay. Then, uh, once again, join the Facebook community, the self recording [00:46:00] band.com/community. And we'll see you next week with another episode. See that .

Different compression ratios for a signal level above the threshold (taken from Wikipedia):

Picture: Iain Fergusson

Mixing With Your Mind (Recommended Book):

The Attack & Release Show (Recommended Podcast):

Malcom's "Beatbox/Mouth/Snare/80s Samples" From The Episode:

The Essential DIY-Recording Gear Guide:

TSRB Free Facebook Community:

Outback Recordings (Benedikt's Mixing Studio and personal website)

Benedikt's Instagram

Outback Recordings Podcast - Benedikt's other podcast

Stone Mastering (Malcom's Mastering Company)

Your Band Sucks (at business) - Malcom's other podcast

Gimme The Beat (The Netflix Documentary Malcom is involved with)

If you have any questions, feedback, topic ideas or want to suggest a guest, email us at: podcast@theselfrecordingband.com

take action and learn how to transform your DIY recordings from basement demos to 100% Mix-Ready, Pro-Quality tracks!

Get the free Ultimate 10-Step guide To Successful DIY-Recording

[…] What Compression Really Does To Your Music And Why You Need To Understand It […]

[…] 61: What Compression Really Does To Your Music And Why You Need To Understand It […]